Ouattara Watts: The Thirty-Year Overnight Sensation

How did an Ivoirian artist Jean-Michel Basquiat discovered in the 1980s suddenly join two of the hottest galleries and become and auction star?

Of all of the surprises that took place during the May sales in New York, one big one—the sale of Ouattara Watts’ Afro Beat from 2011 for a remarkable $781,200 during Christie’s 21st Century Evening sale—has gone almost unremarked upon. There may be legitimate reasons a six-times-estimate sale didn’t register amid the two weeks of $2.7 billion in auctions but significance is not one of them.

The massive jump in Ouattara’s market after more than thirty years of shows and sales would need explaining in any market climate. But with three more works by an artist who was brought to New York by Jean-Michel Basquiat in the late 1980s coming to market in an eight-day period, now would seem like a good time to try to understand why Afro Beat out-performed so dramatically. This week in Hong Kong, Phillips has Intercessor from 2003 on offer with a HKD 800,000 estimate or about the same $100,000 estimate Afro Beat carried. Next week, on June 29, Sotheby’s will be selling Vertigo #11 in London with an estimate of £100,000. Phillips will follow that up in London with No. 1 for Miles from 1997 that carries a slightly lower estimate of £80,000.

These consignments are mostly based upon the success of Christie’s auction. During the New York sale, bidding quickly out-stripped the estimate range before the real action even began. Then there were at least four different bidders—two online, one on a telephone in New York and the winner on a telephone in Hong Kong—above the high estimate who carried it from $200,000 bid to the final hammer price of $620,000.

Ouattara’s sudden market relevance isn’t despite his long presence in the background of the Contemporary art world but because of it. “He slipped through the cracks,” says Isabella Lauria, the Christie’s specialist who handled the consignment of Afro Beat. “He doesn’t make enough noise for himself.”

Lauria is echoing something Kaelen Wilson-Goldie got at in her October Artforum story explaining Ouattara’s rising visibility. Wilson-Goldie quotes Siddharta Mitter who thinks the cracks Ouattara had fallen through were “generational, geographic, stylistic and temperamental.”

Generational because Ouattara was a late arrival to the 1980s Neo-Expressionist scene in New York but he is very much one of them. Geographic because Ouattara is from the Ivory Coast originally and then spent a significant amount of time first in Paris and for the last 30 or so years in New York. “He’s as much a New York artist as he is an African artist,” says Sotheby’s African art expert Hannah O’Leary.

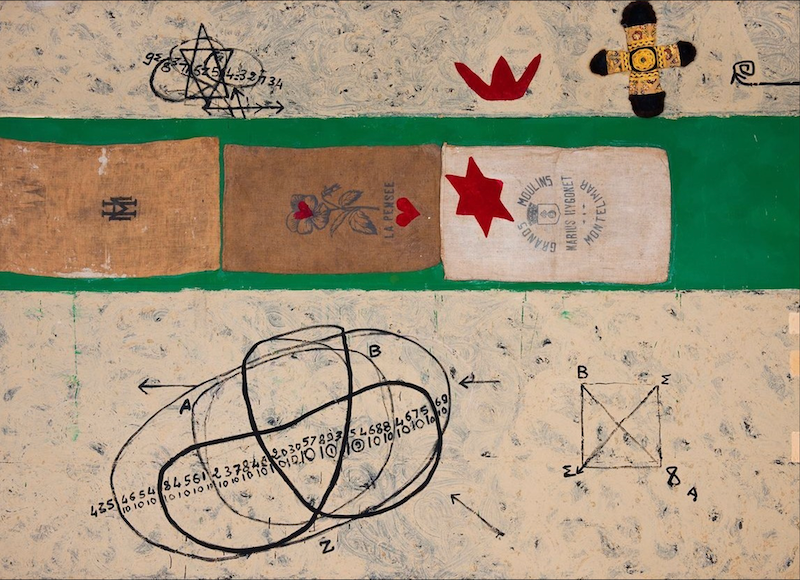

Stylistic because Ouattara’s work melds many references and points of view. He’s as interested in Egyptian hieroglyphics as he is in ancient Greece or mathematics or music and popular culture or references to art history or a wide variety of religious systems including the cosmology of his African upbringing. But he’s not a figurative painter which has been so much in vogue. “When I talk about African figuration to my friends who know about African art,” O’Leary says, “they all laugh because 90% of African art is abstract.”

The final crack was Ouattara’s temperament. During his short-lived but intense friendship with Basquiat, the younger but more famous artist introduced him to his dealers and arranged for Ouattara to have a show in New York. Later he had shows with Gagosian but seemed to prefer to sell work directly from his studio since he enjoyed the patronage of collectors like Claude Picasso and André Putnam, according to Sotheby’s, as well as the interest of other artists like Brice Marden. Though Ouattara seemed to prefer to deal with the famous and the fabulous himself, there were signs that he now recognizes the value of having others do his promotion.

In 2012, Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld held a show of Ouattara’s work during fashion week. At the dinner after the opening, Basquiat’s good friend and the godfather of the 80s downtown scene, Glenn O’Brien, toasted the artist. Dealers Stellan Holm and Alberto Mugrabi looked on. The series of works that were shown by Restoin Roitfeld were called the Vertigo paintings. Christie’s Afro Beat was part of that exhibition.

Sometime after that show and before the recent jump in prices, the Mugrabi family seems to have—the bogeyman of the art market—amassed a double-digit position in Ouattrara’s market. This matters because supply remains an issue. Ouattara’s long career—even without consistent guidance from a powerful dealer—has resulted in a coterie of committed collectors. Few seemed interested in selling when his secondary prices were in the five figures. That’s now changed.

“The stars are aligning for him,” says Rebekah Bowling, Phillips’s specialist handling the two works being offered in Hong Kong and London. The artist has been in prestigious exhibitions before. He was included in Documenta 11 and the Whitney Biennial in 2002, as well as appearing in Venice twice. But like everything else, there's been a renewed interest in Ouattara's work that brought him to last year's delayed Gwangju Biennial.

In 2020, Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi, an artist and curator who works at the Museum of Modern Art, helped arrange the museum’s acquisition of Vertigo #2 (also from the 2012 show—as is the upcoming Vertigo #11 at Sotheby’s.) The donor was Agnes Gund, the museum’s former President and a noted collector. Wilson-Goldie intimates in her Artforum story that Nzewi hopes to repeat the process with other works by Ouattara.

The MoMA acquisition was necessary but not sufficient to create what Christie’s Lauria deemed a “perfect storm” going into her sale. MoMA put Ouattara on view last year (the work has since gone into storage) but the artist still didn’t have strong gallery representation. That changed this Spring. Ouattara has done distribution deals with two dealers known for having a hot hand right now. In late April, the East Village empire of Karma mounted a show of Ouattara’s works. They were followed by Almine Rech which will show the artist in Europe next year but also displayed a large Ouattara at Art Basel Unlimited last week. Both arrangements were known or rumored before the Christie’s auction.

Karma’s Brendan Dugan has a reputation for having good control over where he places work. Even though Ouattara’s secondary market was still in the mid-five figures and Cecile Fakhoury had been selling his work consistently for around $100,000, Dugan priced his works between $150,000 and $220,000. That’s pretty aggressive.

A cynic might suggest the Christie’s sale was being pushed to promote the price level. But a careful review of bidding shows that anyone defending Ouattara’s market would have been left behind at the $200,000 level. Indeed, the Christie’s sale seems to have uncovered more demand than the auction house realized.

LiveArt’s George O’Dell reports seeing active trading in the background between the early May sale and the upcoming action. “It’s the kind of thing you would expect in these discovery markets,” he says, citing private transactions on the platform.

For now, with consignors happy to leave estimates at levels below the current primary market, there are no excessive expectations. Instead, the market seems to be responding to a significant turn or maturation. “We went into lockdown with African art on the periphery,” O’Leary observes. “We came out of it with African artists at the forefront.”

“His biography is in line with what the market wants,” Bowling concurs. By that she means a couple of things. Because Ouattara is equally a 1980s New York nostalgia play like Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, David Salle and even Eric Fischl, there’s a group of collectors who are returning to him as they have in recent weeks, months and years to work by the other four. You could easily throw in Kenny Scharf to that litany.

As the art market moves forward into a new macroeconomic climate, there’s something a great deal more reassuring about collecting an artist with a large body of work to track and collectors who are reluctant to sell. At 65, Ouattara is a known quantity, not someone collectors have to hope will continue to thrive and grow. The institutional recognition was, in many ways, the missing piece of the puzzle.

On the African side, collectors are just beginning to understand the depth of what that generation from that continent has produced. “Where Ouattara came from there are tens of other artists that have been overlooked,” O’Leary says. “There’s still a lot of catching up to do."