Outsider Art Moves Inside

As the Contemporary art market focuses more on the identity and biography of artists, Outsider art is attracting more collectors and bigger dealers.

The Contemporary art world has been on a long-term collision course with the world of Outsider artists for decades. A fascination with artists who lack formal training may be a product of the art world’s interest in representation and authenticity. Or it may just be the culmination of a multi-decade trajectory that at first seemed like parallel paths but now seems to be rapidly converging. Whatever the cause, curators, dealers and collectors are increasingly seeking out artists who work without a conscious connection to art history.

For many years, self-taught artists were a curiosity, prized as much for their isolation —whether in poverty, geography or psychology—as for their artistic vision. Long loosely connected to the Folk Art world, the artists were sold by dealers who specialized in Outsider art. There is even a fair devoted to Outsider art that vets the artists presented by dealers for the originality of their vision and their bona fides as untrained artists.

That’s because there are more Contemporary artists painting in a naive style than ever. And they’re more prized on the market. Along with those artists, mainstream galleries that straddle the continent or the globe like David Zwirner, Barbara Gladstone, Blum & Poe and Venus Over Manhattan have begun to exhibit or represent some of the best-known names in Outsider art like Bill Traylor, Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, Joseph Yoakum or James Castle.

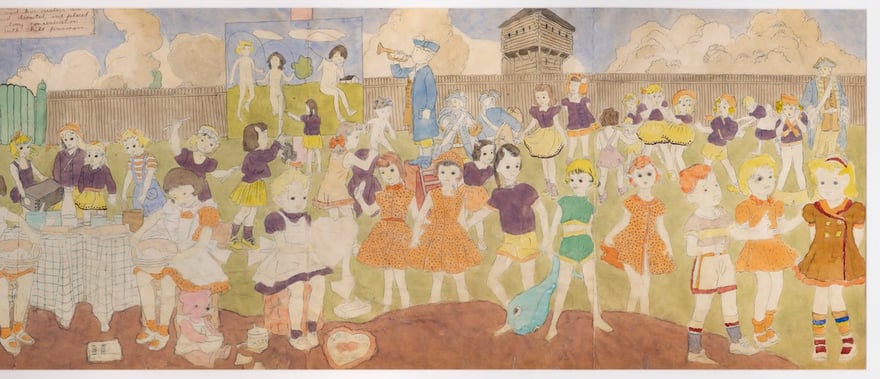

“This feels like more than a cycle to me,” says Andrew Edlin, the gallerist who handles works by major Outsider figures including Henry Darger, another well-known self-taught artist whose work has helped define the field. “It feels like we’re on a one-way course now, it’s not going to go back.” Edlin is also the owner of the Outsider art fair which recently celebrated its 30th year in New York and will also have its 10th anniversary in Paris this September.

Edlin, like many others, has previously seen mainstream interest in Outsider artists. The field grew out of two separate strands. One was folk art which has its own museums and emphasizes craft traditions. The Souls Grown Deep Foundation, the surviving entity animated by super-collector Bill Arnett’s passion, has done as much as any one institution to identify these artists, reclaim their work and steward it into collections private and public.

On the other side of Outsider art lies a fascination with isolated individual artists. Jean Dubuffet got the ball rolling in the 1940s with his interest in what he called Art Brut. It wasn’t until the early 1970s that Roger Cardinal, a scholar of Surrealism, discovered Dubuffet. For 30 years few had paid attention to Dubuffet’s Art Brut but Cardinal made connections between the artist’s ideas and Surrealism. “I went to Paris to get ammunition,” Cardinal reflected in an interview on the three weeks he spent daily reviewing artists from Dubuffet’s own research three to four at a time. “It was like a kind of intellectual raid on Dubuffet.”The cultural walls between the gallery and museum world and other types of art were much higher in 1940s that they are today. That might explain why there was little interest in Art Brut until Cardinal rechristened it with the title of his book as Outsider art.

“A lot of outsider art rotates around issues of personality,” Cardinal said, “of asking who I am, which means going deep into the inner self of an individual.” This same subject, the inner self and the culture that shapes it, had become a central fixation of cultural inquiry by the late 1960s and early 1970s. Philosophers and historians like Michel Foucault became interested in the way power shaped discourse and defined some persons within the rational world and others outside of it. Foucault was famous for his studies of prisons and insane asylums. Later, art historian Douglas Crimp added the museum to this list of institutions of confinement—or, more likely in the case of the museum, exclusion.

Art made by the incarcerated, institutionalized or divinely inspired began to draw interest from mainstream culture. In modern society, these are the outsiders. By the 1980s, an artist like evangelical pastor Howard Finster had become fodder for videos and album covers for alternative bands like REM and Talking Heads. This is part of what Edlin was referring to when he says he’s seen these cycles of interest before.

In the 1990s and 2000s, interest in outsider art grew as Sanford Smith established the Outsider Art Fair in 1993 and the surrounding culture of the West accepted greater difference. Romanticism around extreme ruptures in mental health waned; psychiatry became more informed by brain science. Edlin describes the broader transition in Outsider art from an interest in folk art to a fascination with artists who are unself-conscious in their creativity this way: “It’s not 1940, people are on the internet. They have TV. It’s harder to make a case for cultural immunity. Now, a lot of what’s making them isolated is their brain chemistry, as opposed to physical separation.” In today’s Outsider art community, artists who are neurodivergent are celebrated for their singularity of vision.

Not all Outsider artists are autistic. In the last twenty years, Outsider art has been increasingly embraced by the art world’s thought leaders with curators incorporating Outsider art into Documenta and the Venice Biennale. Massimiliano Gioni’s 2013 Biennale, The Encyclopedic Palace, was built around an Outsider artist, Marino Auriti, whose Babel-like tower was the central metaphor for the futility of the information age. ““Blurring the line between professional artists and amateurs, outsiders and insiders,” Gioni wrote of his curatorial project, “the exhibition takes an anthropological approach to the study of images, focusing in particular on the realms of the imaginary and the functions of the imagination.

Having come from the isolated human endeavor to heart of the art world’s own structures for creating meaning and value, it was almost inevitable, at that point, that collectors and Contemporary art dealers would take notice. Outsider art had been nurtured by passionate dealers like Bill Arnett who researched and reclaimed the work of many of these remote artists.

With broader programs and greater reach among collectors, the larger, well-established Contemporary dealers could make connections between Contemporary artists and Outsider artists even if the work was made without reference to one another. The Contemporary dealers could also elevate prices. As Edlin points out, with established five-figure prices, the big galleries can turn that “into a double or a triple.”

“We’re at a little bit of an inflection point where the big boys have jumped into the arena,” Edlin says. “The art dealing community in the outsider art world can’t go to-to-toe with them.”

Edlin’s not complaining. Though he would love to see a few of the global galleries who represent bona fide Outsider artists take booths at his fair. “There’s not one fair in the world,” he says, “that has the critical support that the Outsider art fair.”

The real point here is that the boundaries between the two fields are falling. And it isn’t just Outsider artists becoming Contemporary artists. One thing Contemporary dealers have learned from the Outsider field is to emphasize the biography of the artist. It’s more than identity. What Outsider art prizes is originality of vision and experience. The same can be said about many of the young artists who are being aggressively collected today.